At the age of 18, high school dropout and Utah native Hal Ashby (the subject of the new documentary Hal) headed out on a journey to find himself, wandering around the American West and taking odd jobs to survive. He wasn’t sure what he wanted to do with his life, but he knew there had to be something out there. Working railroad construction in the notoriously cold winter of 1948-49, Ashby decided Southern California sounded like a much better place to be and hitchhiked down to Los Angeles.

Eventually, Ashby got it into his mind to make movies. He went to the State Employment Office and got a job at Universal Pictures copying scripts. From there, he slowly but surely made his way up the food chain, finally getting an opportunity to direct shortly after he won an Oscar for editing In The Heat of the Night. Although well-received by critics, his directorial debut, The Landlord, did poor business at the box office, partly due to a misleading and ill-conceived promotional campaign. His next film, Harold and Maude, initially met a similar fate before gradually gaining a devoted cult following through word-of-mouth. It went on to make a profit more than a decade after it was originally released and is now revered as a classic.

Ashby’s directorial career flourished throughout the 1970s. His next five films, including classics such as Coming Home and Being There, all picked up multiple Oscar nominations and proved commercially successful (except for the 1976 Woody Guthrie biopic Bound for Glory, in spite of a warm critical reception). However, his career floundered in the 1980s, due at least in part to tensions between him and studio executives and rumors of dysfunctional behavior and cocaine dependence now generally regarded as largely baseless, the product of a malicious whisper campaign. Ashby continued to seek work and attempted to develop a number of projects, but sadly he did not manage to make a comeback before his death from pancreatic cancer in 1988 at the age of 59.

During his grueling, decades-long rise through the ranks from the very bottom all the way to the director’s chair, Ashby learned his fair share of valuable lessons. Here are six of the best:

If You Want To Learn To Direct, Edit

While directing was always the end goal for Ashby once he decided to enter the film industry, it was a long road to get there. Established directors at Universal advised the young Ashby to pursue editing in order to get there. It wasn’t easy, as Ashby had to get into the editor’s union and finish an eight-year apprenticeship before getting to be an editor proper. Ultimately, though, he agreed that it was an ideal way to learn the craft, as he elaborated in an article entitled “Breaking out of the Cutting Room” that he wrote for the September/October 1970 issue of Action magazine:

“When film comes into a cutting room, it holds all the work and efforts of everyone involved up to that point. The staging, writing, acting, photography, sets, lighting, and sound. It is all there to be studied again and again and again, until you really know why it’s good, or why it isn’t. This doesn’t tell you what’s going on inside a director, or how he manages to get it from head to film, but it sure is a good way to observe the results, and the knowledge gained is invaluable.”

Put Story First, Even For Biopics

Ashby found the one biopic of his directorial career, Bound for Glory, presented unique challenges. After struggling to pursue the separate and not always aligned goals of crafting an engaging narrative and being faithful to historical events, he ultimately came to the following conclusion, as elaborated to Pierre Sauvage in a 1977 interview at the Cannes Film Festival, where the film competed for the Palme d’Or:

“Doing a film about a real person drove me crazy at first, trying to be faithful, until I decided I should just do a story about the character.”

End With Ambiguity

The endings of several of Ashby’s films manage to be melancholic without being unpalatably depressing through the use of ambiguity. His 1975 film Shampoo, for example, ends with main character George (Warren Beatty) watching from a hilltop as the woman he loves leaves to run away with another man. Ashby had to fight both Beatty and screenwriter Robert Towne to do the ending his way, as they both wanted to include an epilogue that would solidify the fates of the various characters.

Ashby elaborated on this technique and why leaving Shampoo a bit more open-ended was so important to him to interviewer Rochelle Reed in a 1975 AFI seminar, saying:

“I like to leave a little bit of an enigma there about exactly what it is because I think that’s what makes it not a totally down kind of an ending.”

Filmmaking is a Communal Art

One of the main tenets of Ashby’s philosophy of filmmaking was a wholehearted love of film as a collaborative art. When asked about Ashby, cast and crew members who worked with him frequently discuss how open he was to the ideas of others. Actors in particular note that he gave them considerable say in developing the characters they played. Ashby had the following to say about working with other people in the moviemaking process, as quoted in Hal Ashby: Interviews:

“The great thing about film is, it really is communal. It really is the communal art, and you don’t lose anything—all you do is gain. Your film just gains and gains. The more input you get, the better it is.”

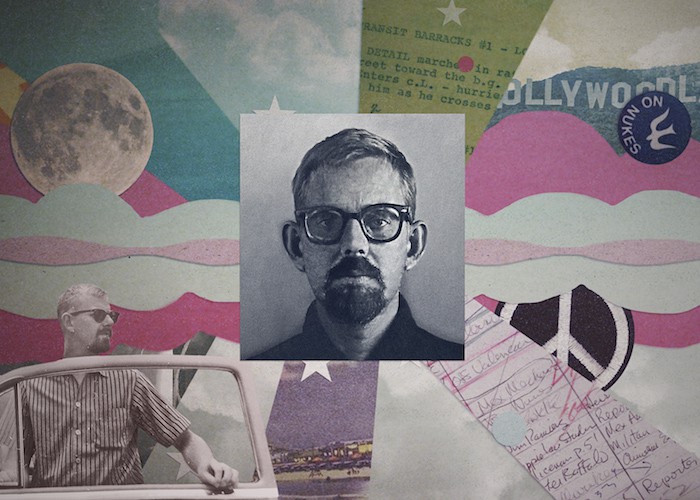

‘Hal’ (Oscilloscope Laboratories)

Identify with Your Characters

Even though he worked with major studios, Ashby’s films were always character-driven personal tales. In a 1978 interview with the Minneapolis Star, Ashby elaborated on his key to developing well-rounded film characters:

“I identify with all my characters in one way or another. I never sat in a wheelchair like a Vietnam veteran, that’s true. But in a sense, I transcend that reality somewhere inside me when I go to make a film like Coming Home. It then becomes what I would do, how I would feel if I were this particular human being in this particular situation.”

Shouting Won’t Help

In addition to gaining a reputation for treating filmmaking as a communal experience where ideas and collaboration are strongly encouraged, Ashby was generally regarded as an atypically calm director who rarely lost his temper. As Ashby elaborated in an interview quoted in the biography “Being Hal Ashby,” he had one major caveat regarding his “relaxed” label, and an important rationale behind staying calm on set:

“I’m not laid back. There’s a tremendous energy going on all the time. What are you going to accomplish by raising your voice? Even if you’re striving for some tense thing in your film, getting the crew tense isn’t going to help. I went through a period in my life where I argued about everything, and I found I wasn’t getting much accomplished.”

What We Learned

There are plenty of lessons to be learned from the life and career of Hal Ashby, and sadly some of them are more uplifting than others. While his peak in the late 1960s and 1970s marks one of the greatest real-life Hollywood underdog stories of hard work and perseverance paying off—but at a cost. All four of his marriages failed, and Ashby was known to consistently put his professional career over his personal life, locking himself away in editing rooms for days at a time. It’s impossible to know if Ashby would have managed to reach the same heights if his work ethic had been different, but it’s very clear that his decisions also damaged and even destroyed many of his closest interpersonal relationships.

Meanwhile, in spite of his considerable talents, reputation for hard work, and a selection of both critical and commercial successes under his belt, it is hard to deny that his fraught relationships with studio executives participated in the demise in his career from which he never recovered. While Ashby was a strong proponent of creative collaboration, there were many regards in which he was not one for compromise—a double-edged sword that both made his career and arguably destroyed it. Ashby’s films speak to his incredible talents, but the trajectory of his career is equal parts inspirational story and cautionary tale.

The post 6 Filmmaking Tips From Hal Ashby appeared first on Film School Rejects.

No comments:

Post a Comment